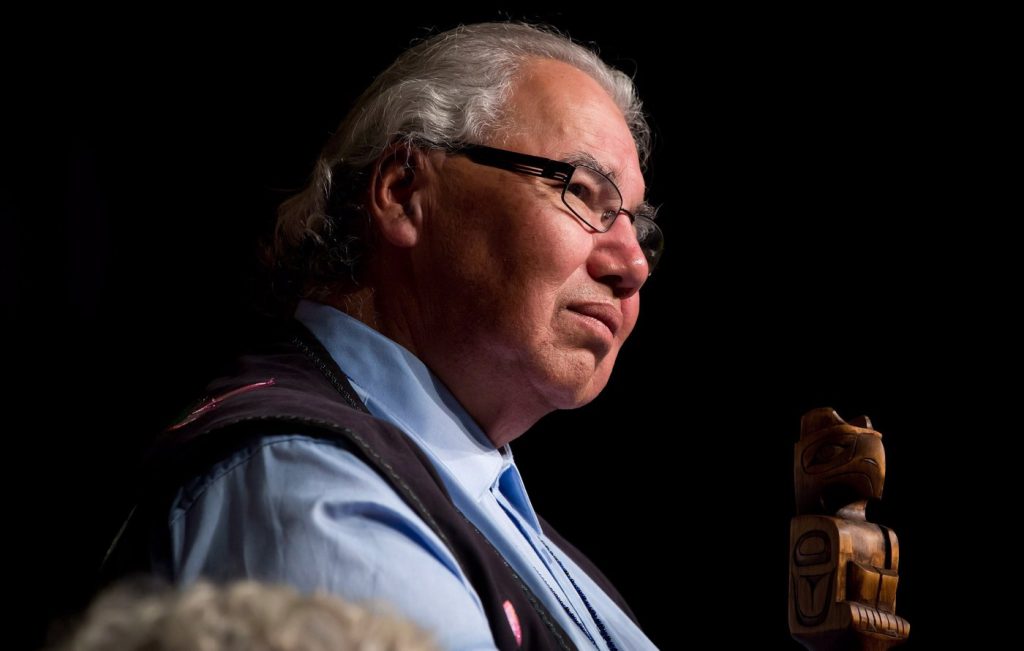

‘The best that we can be’: Indigenous judge and TRC chair Murray Sinclair dies at 73

Posted November 4, 2024 8:53 am.

Last Updated November 4, 2024 11:27 am.

Murray Sinclair, who was born when Indigenous people did not yet have the right to vote, grew up to become one of the most decorated and influential people to work in Indigenous justice and advocacy.

A former judge and senator, one of Sinclair’s biggest roles was chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into residential schools.

The father of five died peacefully Monday morning in a Winnipeg hospital, said a statement from his family.

He was 73.

“Mazina Giizhik (the One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky) committed his life in service to the people: creating change, revealing truth, and leading with fairness throughout his career,” said the statement, noting his traditional Anishinaabe name.

Tributes came in from across the country, including from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

“He challenged us to confront the darkest parts of our history — because he believed we could learn from them, and be better for it,” read a post by Trudeau on X, the social media platform formerly called Twitter.

“We are deeply saddened by the loss of a friend and prominent leader in Canada who championed human rights, justice and truth,” Governor General Mary Simon said.

The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs said Sinclair “broke barriers and inspired countless individuals to pursue reform and justice with courage and determination.”

Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham called Sinclair a leader in justice, education and reconciliation.

“His passing feels especially sad because the journey he started is still ongoing, with much work ahead.”

A sacred fire to help guide his spirit home has been lit outside the Manitoba legislature, said the family.

Born in 1951, Sinclair was raised on the former St. Peter’s Indian Reserve north of Winnipeg. He was a member of Peguis First Nation.

He was raised by his grandparents and graduated from a high school in Selkirk, Man., where he excelled in athletics.

Some of his earliest childhood memories were published earlier this year in his memoir, “Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation.”

In it, Sinclair described discrimination he experienced being Anishinaabe in a non-Indigenous school.

“While I and others succeeded in that system, it was not without cost to our own humanity and our sense of self-respect. These are the legacies all of us find ourselves in today.”

In 1979, Sinclair graduated law school at the University of Manitoba and later became the first Indigenous judge in Manitoba — the second in Canada.

He served as co-chair of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba to examine whether the justice system was failing Indigenous people after the murder of Helen Betty Osborne and the police shooting death of J.J. Harper.

In leading the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he participated in hundreds of hearings across Canada and heard testimony from thousands of residential school survivors.

The commissioners released their widely influential final report in 2015, which described what took place at the institutions as cultural genocide and included 94 calls to action.

“Education is the key to reconciliation,” Sinclair said. “Education got us into this mess and education will get us out of it.”

Two years later, he and the other commissioners received the Meritorious Service Cross for their work.

It was one of many recognitions Sinclair received over his career.

He was given a National Aboriginal Achievement Award, now the Indspire Awards, in the field of justice in 1994. In 2017, he received a lifetime achievement award from the organization.

In 2016, Sinclair was appointed to the Senate. He retired from that role in 2021.

The following year, he received the Order of Canada for dedicating his life to championing Indigenous Peoples’ rights and freedoms.

In accepting that honour, Sinclair said he wanted to show the country that working on Indigenous issues requires a national effort.

“When I speak to young people, I always tell them that we all have a responsibility to do the best that we can and to be the best that we can be,” he said.

Sinclair limited his public engagements in recent years due to declining health.

In his memoir, Sinclair described living with congestive heart failure. Nerve damage led to him relying on a wheelchair.

Sinclair’s memoir was released in September. In it, he continued to challenge Canadians to take action.

“We know that making things better will not happen overnight. It will take generations. That’s how the damage was created and that’s how the damage will be fixed,” Sinclair wrote.

“But if we agree on the objective of reconciliation, and agree to work together, the work we do today will immeasurably strengthen the social fabric of Canada tomorrow.”